Determining the Optimal Pelvic Floor Muscle Training Regimen for Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence

Chantale Dumoulin,1∗ Cathryn Glazener,2§ and David Jenkinson2|| 1Faculty of Medicine, School of Physiotherapy, University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada 2Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK

Pelvic floor muscle (PFM) training has received Level-A evidence rating in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women, based on meta-analysis of numerous randomized control trials (RCTs) and is recommended in many published guidelines. However, the actual regimen of PFM training used varies widely in these RCTs. Hence, to date, the optimal PFM training regimen for achieving continence remains unknown and the following questions persist: how often should women attend PFM training sessions and how many contractions should they perform for maximal effect? Is a regimen of strengthening exercises better than a motor control strategy or functional retraining? Is it better to administer a PFM training regimen to an individual or are group sessions equally effective, or better? Which is better, PFM training by itself or in combination with biofeedback, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, and/or vaginal cones? Should we use improvement or cure as the ultimate outcome to determine which regimen is the best? The questions are endless. As a starting point in our endeavour to identify optimal PFM training regimens, the aim of this study is (a) to review the present evidence in terms of the effectiveness of different PFM training regimens in women with SUI and (b) to discuss the current literature on PFM dysfunction in SUI women, including the up-to-date evidence on skeletal muscle training theory and other factors known to impact on women’s participation in and adherence to PFM training.

Neurourol. Urodynam. 30:746–753, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Key words: pelvic floor muscle training; stress urinary incontinence; women

INTRODUCTION

National and international clinical practice guidelines recommend supervised pelvic floormuscle (PFM) training as a first-line treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women (Level of evidence A).1-4 The goal is to improve the functioning of the PFMs.2 Essentially, PFM training can be prescribed to increase:

- PFM strength (the maximum force generated by a muscle in a single contraction),

- PFM endurance (the ability to perform repetitive contractions or to sustain a single contraction over time), and

- PFM coordination (muscular activity prior to effort and on

exertion), or - any combinations of these.

Supervised by a trained health professional, progressive PFM training involves various PFM exercises either with or without adjunctive biofeedback, electro-neurostimulation, intra-vaginal resistance, and/or a bladder diary.1 The uncertainty about which of these strategies are most effective in training women to use their PFM to cure or improve symptoms of SUI has been identified by a wide panel of patients and experts to be one of the key clinical questions which needs to be prioritized.5

In order to determine the best regimen for treating SUI in women, this study begins with a review of the up-to-date evidence of the effectiveness of PFM training regimens alone as compared to no treatment or a placebo treatment, the evidence for the comparative effectiveness of different types of PFM training regimens and, finally, the evidence for PFM training in combination with various adjunct therapies.

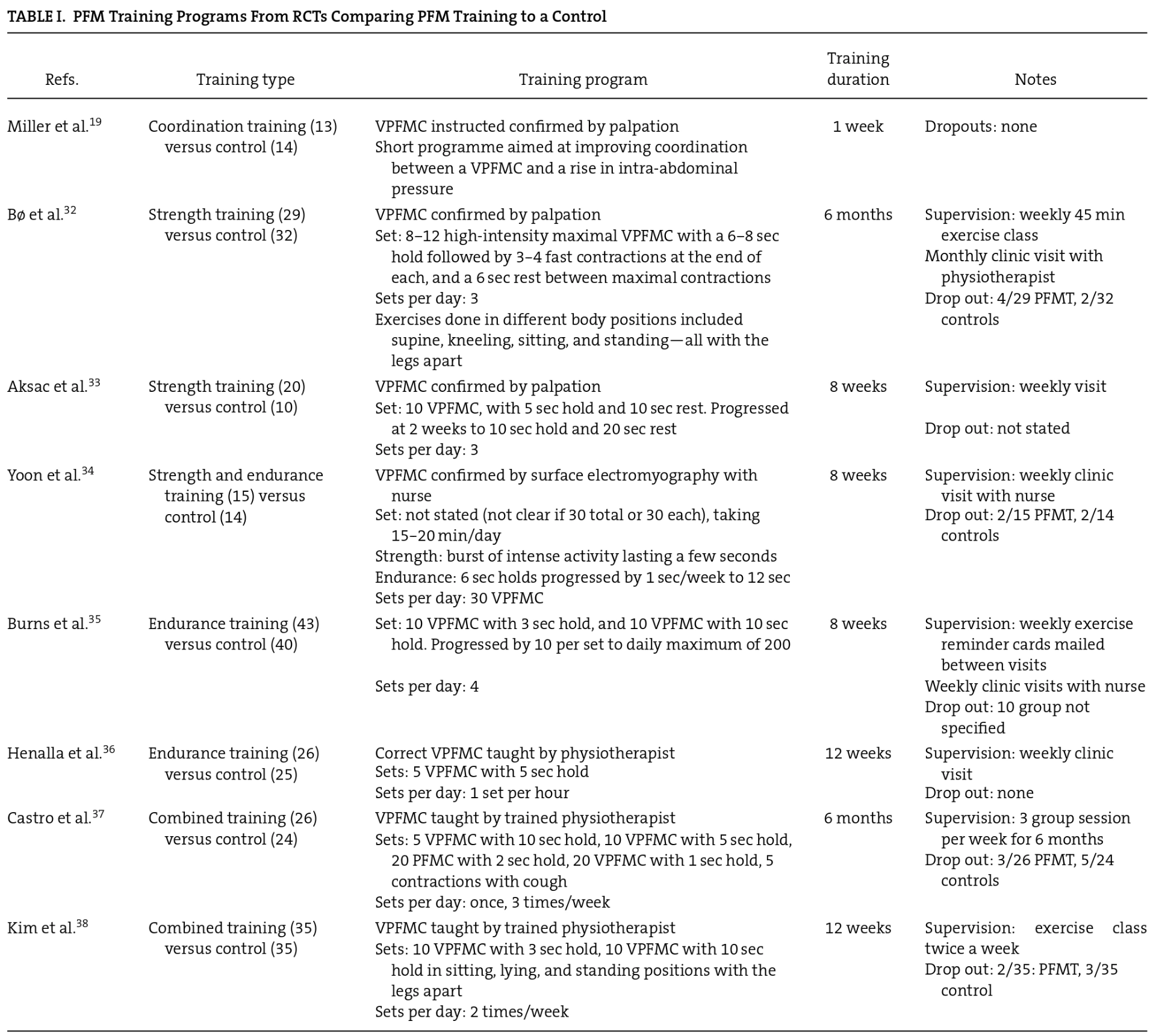

PFM TRAINING ALONE VERSUS NO TREATMENT STUDIES

The effects of PFM training for women with urinary incontinence (UI) as compared to no treatment, a placebo or sham treatment were recently evaluated in a Cochrane Review.2 The Cochrane Incontinence Group’s Specialised Trials Register and the reference lists of relevant articles were searched (February 18, 2009). Randomized and quasi-randomized trials and the targeted population (women with stress, urgency, or mixed UI) were among the selection criteria. In this review, at least one component of each trial had to include PFM training. The comparators were no treatment, a placebo or a sham treatment, or another type of inactive control treatment. Fourteen trials involving 836 women met the inclusion criteria. Within the 14 trials, only 8 (370 women) contributed data exclusively for women with SUI and were also suitable for analysis (Table I). There were considerable variations in the exercise regimens and often their descriptions were not extensive. Generally, the exercise programmes consisted of strength, endurance or coordination training, or a combination of these:

Linda Brubaker led the review process.

Conflict of interest: none.

The work was performed at ICI-RS 2010.

§ Professor of Health Research.

|| Research Fellow.

∗ Correspondence to: Chantale Dumoulin, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Faculte´ de Me´decine, E´cole de Re´adaptation, Universite´ de Montre´al, C.P. 6128 Succ. Centre-ville, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada H3C 3J7. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 3 February 2011; Accepted 15 February 2011

Published online 15 June 2011 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com).

DOI 10.1002/nau.21104

PFM, pelvic floor muscle; VPFMC, voluntary PFM contraction; PFMT, PFM training; Set, one episode or sequence of PFM contractions or training, including length of time of holding contraction, positions while performing contractions and number of repetitions of contractions

- Programmes with a low number of repetitions and high loads (maximal effort) were classiï¬ed as strength training.

- Those that included a high number of repetitions or prolonged contractions with low-to-moderate loads (submaximal contractions) were classiï¬ed as endurance training.

- Those that employed the repeated use of a PFM contraction in response to a speciï¬c situation (e.g., prior to cough, “The Knackâ€) were classiï¬ed as coordination training.

- For the most part, PFM training programmes were difï¬cult to categorize because they described either a mixed (e.g., strength and endurance) programme or omitted a key training parameter (e.g., the amount of voluntary effort per contraction, number or duration of contractions per set, duration or frequency of sets per day, Table I).

Despite these difï¬culties, the review found that PFM-trained women with SUI were about 17 times more likely to report cure of incontinence compared to those having non-active control management in one trial (RR 16.8, 95% CI: 2.4-119.0). Additionally, PFM-trained women with SUI were 17 times more likely to report improvement or cure of their symptoms (RR 17.33, 95% CI: 4.31-69.64, in two trials). Moreover, they experienced between 0.8 and 3 fewer leakage episodes per 24 hr compared to women in non-active treatments. Finally, PFM-trained women with SUI were 5-16 times more likely to be continent on a short pad test than women in non-active treatments.2

Overall, the best conclusion that could be derived from the review is that PFM training is better than no treatment, placebo drug, or inactive control treatments for women with SUI. Variations in the PFM training programmes were a major source of clinical heterogeneity, preventing a comparative analysis of the training programmes and their potential effectiveness. The study trials, however suggested that treatment effects (in terms of self-reported cure/improvement) might be greater in women with SUI participating in a supervised PFM training programme for at least 3 months.2

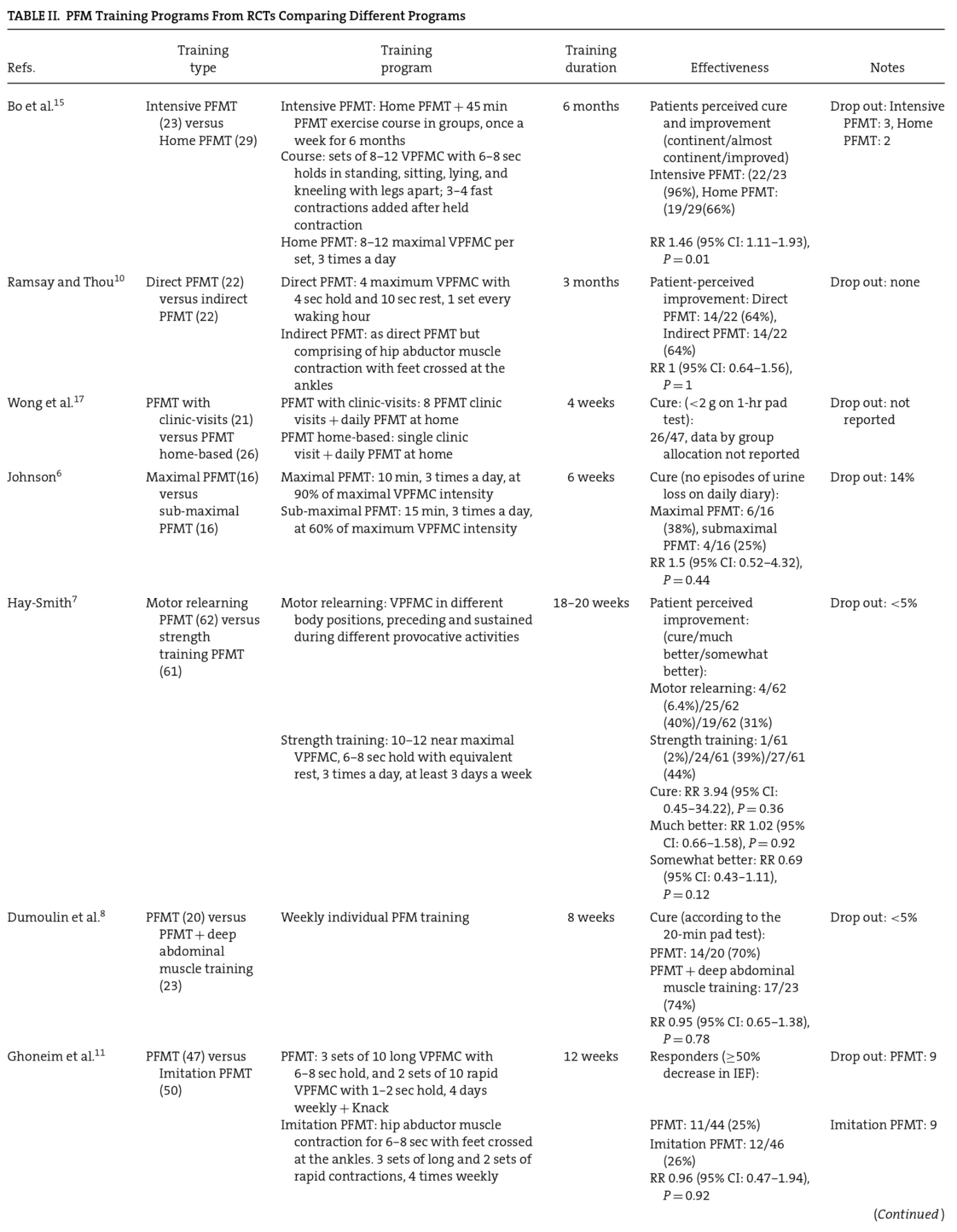

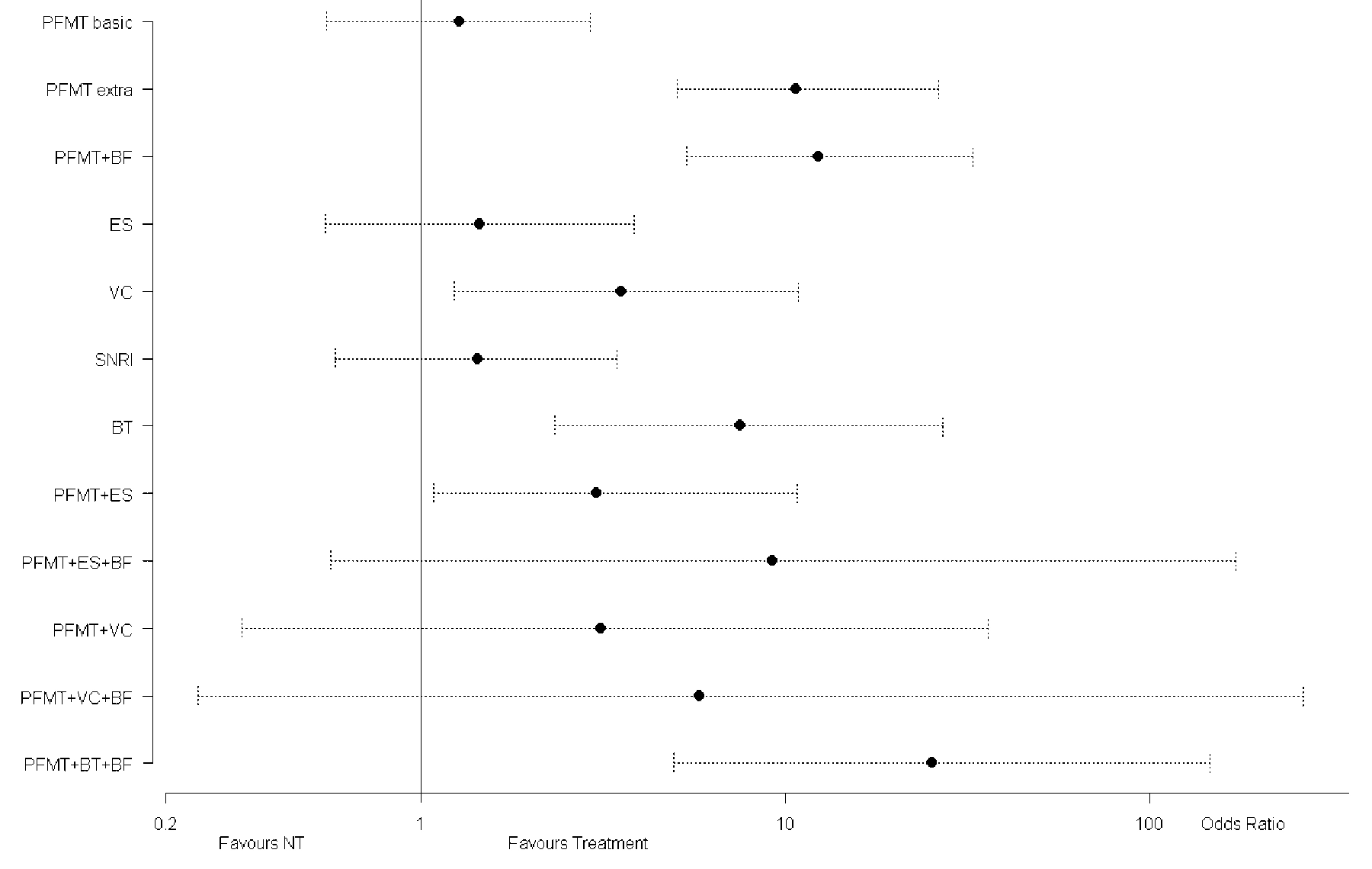

COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT PFM TRAINING REGIMENS

Twelve trials comparing different PFM exercise regimens in SUI women were found in the literature review, very few of which compared the same regimens. In most trials, the participant numbers were few; consequently the conï¬dence intervals were wide and the results were inconclusive (Table II).6-17

Because of this limitation, the review of the available data was unable to discern clear differences between the following training regimens:

- maximal versus submaximal strength training,6

- strength/motor relearning versus motor relearning alone,7

- PFM training with and without deep abdominal muscle training,8

- exercises in the supine position versus a combination of positions (supine, sitting, and standing),9

- direct PFM training versus indirect or imitation PFM training through the hip abductor muscles,10,11 or

- modiï¬ed pilates.12

In contrast, women were more likely to report cure/improvement if PFMT was taught and supervised by a health professional versus self-administered.14 Further, self-reported cure or cure/improvement in SUI women was more likely with more health professional contact during PFMT versus less health professional contact (Table II).15,16

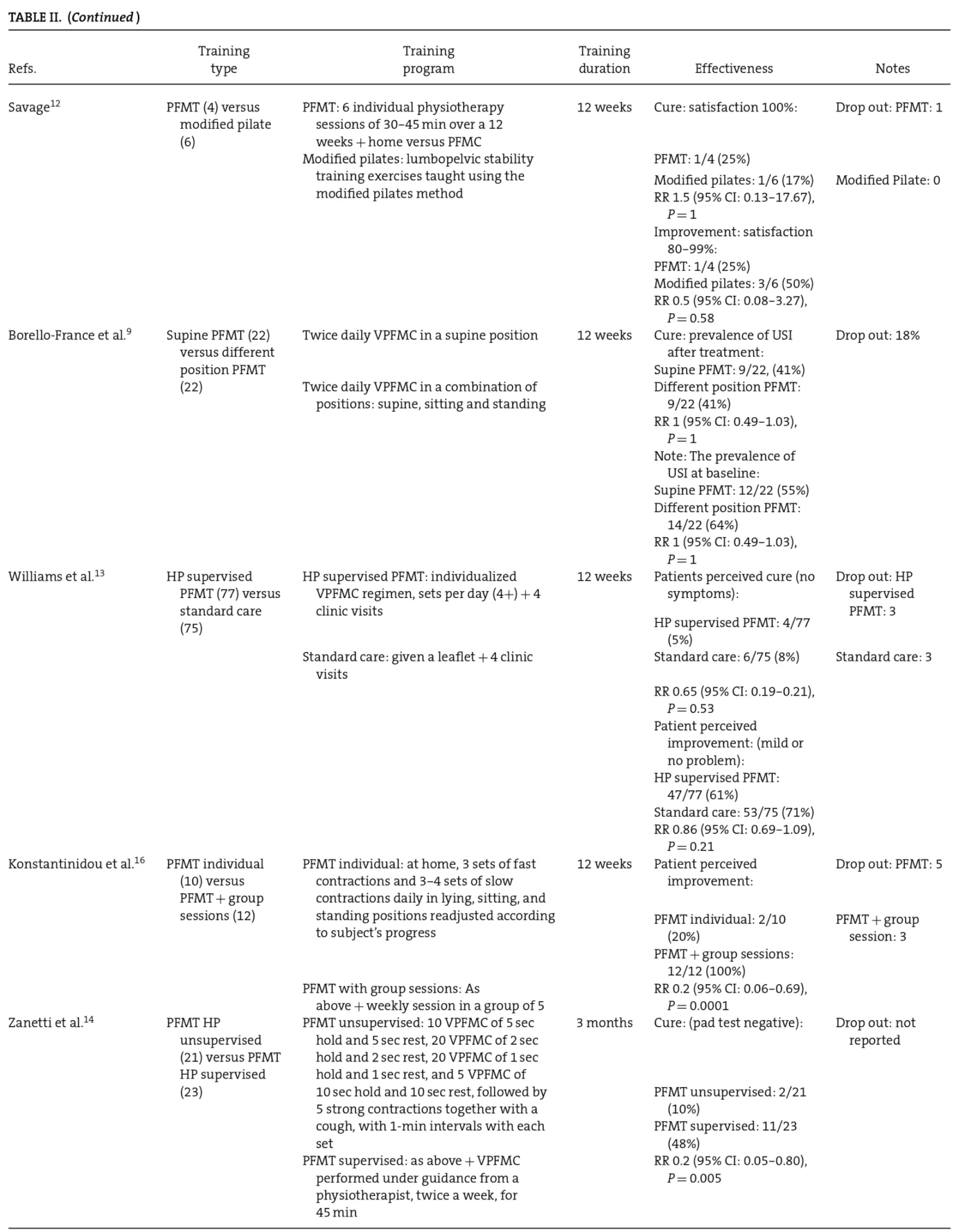

PFM TRAINING IN COMBINATION WITH VARIOUS ADJUNCT THERAPIES STUDIES

More recently, the effectiveness of PFM training combination with various adjunct therapies has been studied using mixed treatment comparison models. These are sophisticated metaanalyses that handle evidence about several interventions from many trials in one analysis, producing comparisons between all pairs of interventions, including those which have not been directly compared in any trial.18 The Cochrane Incontinence Group’s Specialised Trials Register and the reference lists of relevant articles were searched (up to June 2008). Randomized and quasi-randomized trials where more than 50% of participants had SUI were eligible. The primary outcome measures were (1) cure and (2) improvement of the symptoms of SUI. These outcomes were measured in the trials as either patientreported (where available), or clinician-reported (as a proxy for the patient-reported outcome when this was not reported).

Eighty-eight trials were identiï¬ed (9,721 women).18 The mixed treatment comparison analysis compared 14 interventions (including “no active treatmentâ€) and included data from 55 trials (6,608 women) that reported cure or improvement. Interventions were on average more effective than no treatment. Further, there was clear evidence that PFM training either with extra sessions (more than 2 per month) or combined with biofeedback, was better than no treatment, for cure of incontinence, while a basic frequency of PFM training sessions (2 or less per month) was not. Vaginal cones, bladder training, PFM training with electrical stimulation and PFM training with both bladder training and biofeedback were also more likely to cure incontinence than no treatment (Fig. 1). Furthermore, all of the interventions examined (with the exceptions of PFM training with vaginal cones and biofeedback, and PFM training with Duloxetine), were signiï¬cantly better than no treatment at improving SUI (HTA monograph18 Fig. 32, p. 105). Moreover, there was also clear evidence that when women attended for PFM training in more than 2 sessions per month it was more effective than 2 or fewer sessions per month (cure: median odds ratio 8.36, 95% credible interval 3.74-21.7; improvement: median odds ratio 5.75, 95% credible interval 2.11-16.2). Therefore, PFM training reinforced with biofeedback or PFM provided in extra sessions appear to be the most effective interventions, although there is some uncertainty surrounding this.18

So in summary, in terms of treatments speciï¬cally targeting women with SUI, the up-to-date evidence does not clearly identify an optimal PFM training regime. However, the evidence does suggest that supervised PFMT programmes delivered more often (more than 2 sessions per month) or augmented with biofeedback appear to be more effective. In order to identify the parameters of an optimal PFM training, rigorous adequately powered RTCs must be conducted in which different models of PFM training regimens are compared.

This being said, there are, however, certain elements in the literature pertaining to (a) the biological rationale for PFM training, (b) PFM dysfunction in women with SUI, (c) skeletal muscle training theory as progressive overload, and (d) behavior and adherence strategies which impact on women’s participation and adherence to PFM training programmes. These are discussed in detail below and must be taken into consideration when designing optimal PFM training regimens which might be amenable to testing by randomized control trial (RCT).

BIOLOGICAL RATIONALE FOR PFM TRAINING

The biological rationale for using PFM training is twofold. Firstly, a voluntary contraction before and during a cough (a maneuver termed “The Knackâ€) has been shown to effectively reduce urinary leakage during a cough.19 Hence, simply learning to contract the PFM before a cough may be, in and of itself, sufï¬cient treatment for those women who experience leakage during coughing; and as such should be included in all PFM training regimens for SUI women. Secondly, improving PFM strength is thought to build up long-lasting structural support of the pelvis by elevating the levator plate to a higher location in the pelvis: this is also enhanced by hypertrophy of the muscles which will increase the stiffness of the PFMs and connective tissues.20 Thus, improving PFM strength could prevent perineal descent during increased intra-abdominal pressure and facilitate PFM before and during effort, thereby reducing SUI in women. Given the above biological rationale, when treating SUI the focus of any PFM training should be to improve the timing (of the contraction relative to a stressor), strength, and stiffness of the PFM.

PFM DYSFUNCTION LITERATURE IN WOMEN WITH SUI

Further to the biological rationale, a growing body of literature focuses on the differences in PFM function in continent and SUI women. Using instruments such as dynamometers, which can provide direct measurements of PFM function (muscle tone, strength, coordination, and endurance), and other innovative technologies such as ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), these studies have provided a unique way of studying PFM function, displacement, and morphological integrity in continent women versus those with SUI. Such studies have already increased our understanding of SUI pathophysiology, determined the causes of functional abnormalities, and might, in future, enable us to identify and better tailor PFM training regimens to SUI women. Some examples include:

PFM, pelvic floor muscle; VPFMC, voluntary PFM contraction; PFMT, PFM training; HP, health professional; Set, one episode or sequence of PFM contractions or training, including length of time of holding contraction, positions while performing contractions and number of repetitions of contractions.

Fig. 1. Mixed treatment comparison: odds ratio for cure of urinary incontinence for each treatment versus no treatment. Posterior distributors median (circle) with 95% central credible intervals. The horizontal axis is plotted on the log scale. PFMT basics: ≤2 sessions per month; PFMT basics: >2 sessions per month; VC, vaginal cones; SNRI, Duloxetine; BF, biofeedback; BT, bladder training; ES, electrical stimulation.

In a cohort study evaluating PFM function in 59 premenopausal women, using dynamometry, Morin et al.21 demonstrated that incontinent women as compared to continent women had lower passive force at rest (muscle tone), showed lower endurance, and were unable to produce as many rapid contractions in 15 sec; indicative of PFM dysfunction at rest and during an active contraction.

In another study by the same author, which evaluated PFM function in 34 continent women and 33 post-menopausal women with SUI, incontinent women showed a reduction of the PFM involuntary response during a maximal cough such as a lower PFM-contraction rapidity, a decrease in maximal PFM force, and a reduction of the PFM force measured at peak maximum intra-abdominal pressure. This indicates abnormalities in the involuntary responses of the PFM during coughing in women with SUI.22

Conversely, Verelst and Leivseth,23 in a study evaluating PFM function using dynamometry on 26 control and 20 SUI parous women, concluded that normalized strength differed between continent and SUI women; the incontinent women had weaker PFMs.

Further, in Lovegrove et al.24 used US to characterize the displacement, velocity, and acceleration of the PFM during a cough in 23 asymptomatic and 9 SUI women. They found that during a cough, PFM activation in continent women produced a timely compression of the PFMs and provided additional external support to the urethra, reducing displacement, velocity, and acceleration. In women with SUI, this PFM pre-contraction did not occur; consequently, the urethras of women with SUI had to move further and faster for a longer duration.

Finally, using MRI, Hoyte25 found differences between continent and SUI women in terms of the position of the levator plate at rest, which is indicative of stiffness; the levator plate being higher in continent women.

All these ï¬ndings indicate that PFM function is deï¬cient in SUI women at rest (in terms of tone and stiffness), during a maximal voluntary contraction (maximal strength, rapidity, and endurance), and during effort (timing and maximal strength). Therefore, PFM assessments could be used to identify which aspects of structure or function are deï¬cient; subsequent training regimens could then be designed to address these dysfunctions by using a diversity of exercises, possibly tailored to individual women’s abilities. Ultimately, the development of clinical prediction rules based on such assessments could improve clinical practice, enabling SUI women to be matched to the optimal intervention for their condition.

SKELETAL MUSCLE TRAINING THEORY AS PROGRESSIVE OVERLOAD

The American College of Sports Medicine recently issued a special communication on evidence-based progression models for resistance training in healthy adults.26 These recommendations could be used to elaborate exercise regimen protocols aimed at improving timing, strength, and stiffness. The article sets out the basic principles, including progressive overload, speciï¬city, and periodization, that need to be incorporated into any resistance-training programme in order to achieve maximum results.

PFM training regimens should also adhere to these principals. For example, in relation to PFM training, progressive overload implies that the intensity of the exercises and the number of repetitions should be gradually increased throughout the exercise programme, the speed or tempo of the repetitions with submaximal loads should be adjusted according to the desired goal (i.e., to train for either endurance or strength), the rest periods should be shortened for endurance-improvement training or lengthened for strength and power training, and, ï¬nally, the overall volume of training should be increased gradually.

Further, in order to increase muscle strength, the progression model suggests using a repetition range of 8-12 maximum contractions at moderate velocity, a 1- to 2-min rest between sets, an initial training frequency of 2-3 times per week progressing to 4-5 times, and the application of a 2-10% increase in load when an individual can perform the current workload for 1-2 repetitions over the targeted number.

For endurance training, the progression model suggests the need for light to moderate loads (40-60% of maximal load) with high repetitions (>15) and short rest periods (<90 sec). In PFM training this can be achieved by changing positions from gravity-free to anti-gravity (i.e., from lying to sitting to standing) or through the introduction of cones into the exercise sessions.

Finally, rapidity and coordination training (“The Knackâ€) would include the use of repetitive, voluntary PFM contractions in response to speciï¬c situations; for example, prior to and during coughing, lifting an object, or jumping.

TYPES OF BEHAVIOR AND ADHERENCE STRATEGIES FOR EFFECTIVE PFM TRAINING

A few studies have examined factors that impact on women’s participation in and adherence to a PFM training regimen during treatment (in class and at home), as well as in the longterm, post-treatment.27-29 In a qualitative descriptive study using individual and focus-group interviews, In 2006, Milne and Moore27 studied the self-care strategies employed by community-dwelling individuals to adhere to the PFM training regimen at home. Factors that facilitated home-based PFM training included realistic goals and expectations, positive afï¬rmations, follow-up, and a regular exercise routine. Barriers noted were insufï¬cient information about the exercise, the characteristics of the exercises, competing interests, ï¬nancial costs, and minor psychosocial impacts.27

In 2007, Martin and Dumoulin28 also studied factors that facilitate or impede the participation of women with UI in a weekly PFM-exercise classes and their adherence to a daily, home-based PFM exercise programme. Four facilitating factors in terms of participation in a weekly PFM exercise classes were identiï¬ed: a desire to reduce UI, a sense of responsibility towards the programme, close supervision by a physiotherapist, and group support. Impediments were illness, medical appointments, and planned social activities. Facilitators for the home-based PFM exercise programme were a desire to reduce UI and commitment to making exercises part of a daily routine. Impediments were a busy schedule, the length of the exercise programme, and illness.

Hines et al.29 conducted a survey 1-year post-treatment of 164 community-dwelling, post-menopausal women to identify predictors of long-term adherence to PFM and bladder training exercises. Results indicated that women incorporated PFM training into their lives using either a routine or ad hoc approach. Those participants who used a routine approach were 12 times more likely (than those employing an ad hoc approach) to have a high adherence level at 3 months (OR=12.4, 95% CI=4.0-38.8, P < 0.001) and were signiï¬cantly more likely to have maintained that level 12 months post-intervention (OR=2.7, CI=1.2-6.0, P < 0.014). Practicing bladder training was also related to high adherence.

Finally, two trials have investigated the use of adherence strategies as a means of rendering PFM training more effective in women with SUI. In both trials, two groups followed the same daily home-based PFM training programme, but one was provided with an adherence strategy.30,31 In the Sugaya study, participants were provided with a device emitting a rhythmic beep, signaling them to undertake a contraction; they also pressed a button on the device to record each contraction.30 Participants in the Gallo study were given an audiotape of exercise instructions that counted out 25 consecutive PFM contractions.31 Participants who used the beeping device to cue PFM contractions were more compliant and more likely to be satisï¬ed with the treatment outcome, compared to the control group (RR 3.17, 95% CI: 1.02-9.88).30 Those who used the audiotape of exercise instructions were more likely to perform the exercises twice daily, as per instruction (RR 7.05; 95% CI: 2.78-17.88).31 Whether these adherence strategies impact on objective continence outcomes remains inconclusive, as the results were not signiï¬cant in Sugaya’s study and impact was not measured in Gallo’s.

Interestingly, the ability to incorporate an exercise regime into one’s daily routine or using an adherence strategy were both facilitators for adherence to the home-based exercise programme, including its continuation post-treatment. Results from these studies should be taken into consideration when deï¬ning protocols for PFM training regimens to achieve optimal participation during training, at home and, most importantly, post-treatment.

CONCLUSION

PFM training has been shown to be effective in treating SUI in women. However, to date there are only limited indications as to which type of PFM training is the most effective. While supervised PFM training which is delivered more often (more than 2 sessions per month) or augmented with biofeedback appear to be more effective, data and hence consensus are lacking as to which elements of a PFM training regimen are most effective, such as the strength and duration of the muscle contractions, the type of training employed, the number of contraction repetitions used, the positions in which exercises are performed, the inclusion or exclusion of the use of ancillary muscles (such as abdominal ones), and the treatment session approach (e.g., individual versus a class approach), among many others. Moreover, factors and treatment strategies that affect compliance and long-term adherence are only just beginning to be examined.

It is no longer a question of whether PFM training programmes work but what components (including adjunct therapies) and combinations thereof are most effective. Nor can PFM training be studied without due consideration of PFM dysfunction, resistance training and adherence factors and strategies, derived from physiological theory and innovative technological investigations. Future RTCs which incorporate methods and strategies that have been shown to be effective, both for treatment for and to encourage long-term adherence, are needed to address some of the uncertainties in how best to treat women with SUI.

PFM training programmes work but the how and for whom is still ill understood. In order to improve treatment for SUI women more studies in the following areas are required:

- Which PFM components impact, and to what degree, on the success of PFM training: strength and duration of the muscle contractions, number of contraction repetitions, exercise positions, inclusion or exclusion of ancillary muscles, and individual versus group treatment approach?

- Do adjunct therapies make PFMT more effective; and is success really linked to frequency of contact with health professionals?

- Which clinical and patient-speciï¬c characteristics determine the effectiveness and acceptability of PFM training?

- Which, if any, PFM assessment indicators best predict patient-speciï¬c outcomes enabling clinicians to better match women to the optimal intervention for their condition and individual characteristics?

- Which physiological and psychological factors and/or treatment strategies influence compliance and long-term adherence to a PFM exercise regimen?

REFERENCES

- Hay Smith J, Berghmans B, Burgio B, et al. Adult conservative management in Incontinence, 4th edition. P. Abrams, L. Cardozo, S. Khoury, A. Wein (Eds.). 2009; ISBN 0-9546956-8-2.

- Dumoulin C, Hay Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;CD005654.

- Schr¨oder A, Abrams P, Andersson KE, et al. Incontinence in women. Guidelines on urinary incontinence. Arnhem, The Netherlands: European Association of Urology (EAU); 2009. p.28-43.

- Lucas M, Bosch R, Cruz F, et al. 2010. Addendum to 2009 urinary incontinence guidelines. Arnhem, The Netherlands: European Association of Urology (EAU); 2010. p.4.

- Buckley BS, Grant AM, Tincello DG, et al. Prioritizing research: patients, carers, and clinicians working together to identify and prioritize important clinical uncertainties in urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29:708-14.

- Johnson VY. Effects of a submaximal exercise protocol to recondition the pelvic floor musculature. Nurs Res 2001;50:33-41.

- Hay-Smith EJ. Pelvic floor muscle training for female stress urinary incontinence [PhD]. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Department of Physiotherapy; 2003.

- Dumoulin C, Morin M, Lemieux MC, et al. Efï¬cacy of deep abdominal training when combined with pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence: a single blind randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the 3rd International Consultation on Incontinence. Monaco Progre`s Urol 2004; 14:16.

- Borello-France DF, Zyczynski HM, Downey PA, et al. Effect of pelvic-floor muscle exercise position on continence and quality-of-life outcomes in women with stress urinary incontinence. Phys Ther 2006;86:974-86.

- Ramsay IN, Thou M. A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises in the treatment of genuine stress incontinence (Abstract). Neurourol Urodyn 1990;9:398-9.

- Ghoniem GM, Van Leeuwen JS, Elser DM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine alone, pelvic floor muscle training alone, combined treatment and no active treatment in women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol 2005;173:1647-53.

- Savage AM. Is lumbopelvic stability training (using the Pilates model) an effective treatment strategy for women with stress urinary incontinence? A review of the literature and report of a pilot study. J Assoc Chartered Physiother Women’s Health 2005;33-48.

- Williams KS, Assassa RP, Gillies CL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of pelvic floor therapies for urodynamic stress and mixed incontinence. BJU Int 2006;98:1043-50.

- Zanetti MR, Castro RA, Rotta AL, et al. Impact of supervised physiotherapeutic pelvic floor exercises for treating female stress urinary incontinence. Sao Paulo Med J 2007;125:265-9.

- Bo K, Hagen RH, Kvarstein B, et al. Pelvic floor muscle exercise for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: III. Effects of two different degrees of pelvic floor muscle exercises. Neurourol Urodyn 1990;9:489-502.

- Konstantinidou E, Apostolidis A, Kondelidis N, et al. Short-term efï¬cacy of group pelvic floor training under intensive supervision versus unsupervised home training for female stress urinary incontinence: a randomized pilot study. Neurourol Urodyn 2007;26:486-91.

- Wong KS, Fung BKY, Fung ESM, et al. Randomized prospective study of the effectiveness of pelvic floor training using biofeedback in the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence in Chinese population (Abstract). Proceedings of the International Continence Society (ICS), 27th Annual Meeting, 1997 Sep 23-26 Yokohama, Japan, pp. 57-8.

- Imamura M, Abrams P, Bain C, et al. Systematic review and economic modelling of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-surgical treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:97-108.

- Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. A pelvic muscle precontraction can reduce cough-related urine loss in selected women with mild SUI. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:870-4.

- Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle training is effective in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, but how does it work? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2004;15:76-84.

- Morin M, Bourbonnais D, Gravel D, et al. Pelvic floor muscle function in continent and stress urinary incontinent women using dynamometric measurements. Neurourol Urodyn 2004;23:668-74.

- Morin M, Dumoulin C, Gravel D, et al. Reliability of speed of contraction and endurance dynamometric measurements of the pelvic floor musculature in stress incontinent parous women. Neurourol Urodyn 2007;26:397-403, discussion 404.

- Verelst M, Leivseth G. Force and stiffness of the pelvic floor as function of muscle length: a comparison between women with and without stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2007;26:852-7.

- Lovegrove Jones RC, Peng Q, Stokes M, et al. Mechanisms of pelvic floormusclefunction and the effect on the urethra during a cough. Eur Urol 2010;57:1101-10.

- Hoyte L, Schierlitz L, Zou K, et al. Two and 3-dimensional MRI comparison of levator ani structure, volume, and integrity in women with stress incontinence and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:11-9.

- Ratamess NA, Alvar BA, Evetoch T, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position stands—progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:687-708.

- Milne JL, Moore KN. Factors impacting self-care for urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs 2006;26:41-51.

- Martin C, Dumoulin C. Factors impacting incontinent women’s participation to a pelvic floor muscle exercise class and home program. Abstract book, World Congress of Physical Therapy (WCPT), Vancouver. 2007.

- Hines SH, Seng JS, Messer KL, et al. Adherence to a behavioral program to prevent incontinence. West J Nurs Res 2007;29:36-56, discussion 57-64.

- Sugaya K, Owan T, Hatano T, et al. Device to promote pelvic floor muscle training for stress incontinence. Int J Urol 2003;10:416-22.

- Gallo ML, Staskin DR. Cues to action: Pelvic floor muscle exercise compliance in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 1997;16:167-77.

- Bo K, Talseth T, Holme I. Single blind, randomised controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no treatment in management of genuine stress incontinence in women. BMJ 1999;318:487-93.

- Aksac B, Aki S, Karan A, et al. Biofeedback and pelvic floor exercises for the rehabilitation of urinary stress incontinence. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003;56:23-7.

- Yoon HS, Song HH, Ro. YJ. A comparison of effectiveness of bladder training and pelvic muscle exercise on female urinary incontinence. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:45-50.

- Burns PA, Pranikoff K, Nochajski TH, et al. A comparison of effectiveness of biofeedback and pelvic muscle exercise treatment of stress incontinence in older community-dwelling women. J Gerontol 1993;48:M167-74.

- Henalla SM, Hutchins CJ, Robinson P, et al. Non-operative methods in the treatment of female genuine stress incontinence of urine. J Obstet Gynaecol 1989;9:222-5.

- Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MR, et al. Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active treatment in the management of stress urinary incontinence. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2008;63:465-72.

- Kim H, Suzuki T, Yoshida Y, et al. Effectiveness of multidimensional exercises for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in elderly community-dwelling Japanese women: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1932-9.